By Nili Belkind and Edwin Seroussi in collaboration with Hadas Bram and Netanel Cohen-Musai.

The following entry is part of our project on Ezra Aharon’s life and legacy supported by the Israel Academy of Sciences, grants 786/21 (2021-2024: Between Baghdad and Jerusalem: Migration, Cosmopolitanization and Nationalization of Arab/Jewish Music through the Archive of Ezra Aharon) and 1174/24 (2024-2029: Music, Muslims, Jews: Exploring Past and Contemporary Relationalities). For more information, see also the project “Music, Muslim, Jews.”

A more extensive autobiographical account of Azuri al-Awad / Ezra Aharon—compiled from his own writings, recollections, and interviews—is available here.

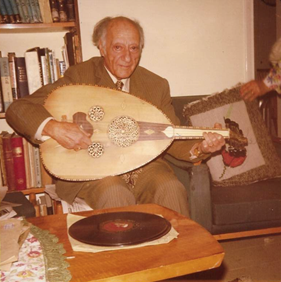

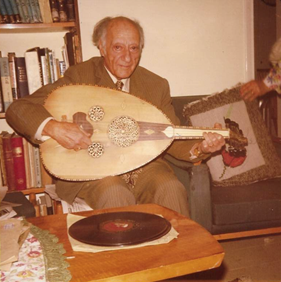

Ezra Aharon, aka Azzori (‘Azzūrī, i.e. Ezra in Arabic)[1] al-Awad (the ‘ud player), son of Aharon ben Shalom Shashoua (Sha’shu’a) was born in 1903 in Baghdad, which was then under Ottoman rule. The Jewish community he was born to was undergoing a period of increased prosperity and social transformation that followed the social reforms of the Ottomans (“tanzimat”) and growing presence of European colonial powers (especially Britain) in the city. At the time of his birth the Jewish community of Baghdad numbered around 50,000, about a third of Baghdad's population (Kadourie 1971).

Most of what we know about Azuri’s life is based on a series of autobiographical sketches focused prominently on his early life found in his archive,[2] and a series of interviews with academics (Gerson Kiwi 1937; Warkov 1981; Shiloah 1981) and journalists (Tidhar 1947; Gorali 1949; Morad 1950; Ben Haim 1960/1) conducted over a span of almost half a century. Scholars who have met Azuri in person or referred to him in their publications (Warkov 1987; Hirshberg 1995; Shiloah 2003; Barth 2012; Dori 2020) also addressed his career and works as part of relevant research projects. All these interlocutors were highly proactive in “translating” Azuri to the readers while prioritizing certain agendas. Some of these writers have framed Azuri within the revival of Hebrew culture in Palestine/Israel while others engaged on the politics of Jewish ethnic identities by hailing Azuri as a prominent Arab Jewish artist and stressing his role in the history of Iraqi and, more general, Arab music.

In our research project, we added an ethnographic layer to these primary sources by interviewing individuals who are related to Azuri via family ties, have been his disciples, or are younger musicians and cultural activists who are engaged with his legacy. Cross-checking these testimonies, with Azuri’s archive at the National Library of Israel (NLI) and data collected via search engines (notably the Historical Jewish Press database) have enabled us to examine critically the diverse narratives about Azuri that have been circulated by our predecessors. Our approach seeks to interpret Azuri’s life and music within the larger context of Arab music history in the twentieth century and the local, transnational and cross-denominational relationalities that contextualize it.

Aharon’s family was well off financially, as his father was a merchant and partner in a tea factory and also involved in international trade between sites within the British Empire’s Asian territories. Ezra attended the Alliance Israelite Universelle School in Baghdad, which meant that he was exposed to Western cultural values, education and languages from an early age. Having enrolled Azuri in such a school means that Aharon’s family did not expect him to become a Torah scholar. Yet, as with all Jews of Baghdad, Azuri was exposed to religious practices and schooling, a foundational upbringing that manifested in his use of rabbinical figures of speech, religious poetry, and even, in his occasional performance as a prayer leader, later in life.

Like many Arab Jews of his generation who have abandoned Orthodoxy but remained observant and respectful of traditional customs, Ezra’s path as a Jew exhibits ambivalence towards faith and religious practice. Moshe Habusha—probably one of the last and perhaps also the youngest among Aharon’s disciples—reports that Ezra blessed God after every meal as customary among religious Jews but instead of reciting the mandatory Grace of Meals, he blessed the Almighty in Arabic with the formula !سبحانك يا ربّ للأبد (Glory be to You, oh Lord, forever!). This ambivalence also resonates in Habusha’s recollection that “during the [British] Mandate [Azuri] lived near the Ohel Rachel synagogue [a main sanctuary for Iraqi Jews in Jerusalem], so kids used to come knocking on his door and ask him to chant a part of the prayer. So, he would come [to the synagogue]. Then he would take a car to work, he worked on Sabbaths…” Habusha added, quoting Azuri’s second wife (and keeper of his archive) Shula: “Ezra said ‘I’m a heretic (apikores), I don't believe in anything’, and yet he would get up in the middle of the night to recite songs from the Book of Psalms.”

Azuri spent his childhood, as he expressed to ethnomusicologist Edith Gerson Kiwi (1937), “living next to the Tigris,” the mythological river of Baghdad which he learned to love and apparently longed for throughout his life away from his city of birth. In Azuri’s accounts, the river, revered as a source of life for the peoples of Mesopotamia since antiquity, also played an almost magical source and resource in his musical career. As a child he had no money to purchase his own instrument but one day, while sitting in the park next to the river, “he saw a broken instrument floating in the water. Taking it out of the river, he saw it was a discarded lute [oud]. He took it, managed to repair it and played on it day and night.” (Gerson Kiwi 1937) Romantic as this story may be, it seems that his first ‘ud was given to him by an older brother when Azuri was a young teenager.

At the same time, most testimonies highlight that Azuri’s family was staunchly opposed the idea of him becoming a musician. One account reports that his father, a very observant Jew, even beat him severely for engaging with music instead of Torah (Gerson Kiwi 1937). By another account, his father, who, as we have noted was a prominent businessman, was disappointed with the likelihood that his son would not wish to join the family business. Ezra maintained that the early death of his father, when he was ten years old, “liberated” him to fully engage with music.

Azuri studied music with one or two Turkish teachers, one of them named Ibrahim Bey, in Baghdad or, as stated in another version, in Istanbul (Ben Haim 1960/1). His music education included theory of Arabic and Turkish music, some Western music theory (as music notebooks in the archive show), as well as learning Western musical notation, a technique that he commanded superbly.

Aharon’s professional career in Baghdad picked up rapidly. At the age of nineteen (1922) he had already performed for the recently crowned King Faisal I, an event that marked the beginning of a productive relationship with the royal house that endured until King Faisal’s death. Beyond the court, in the 1920s and early 1930s Ezra was actively composing and performing for diverse social circles of Baghdad, including the lounges of luxurious hotels which served as sites of musical innovations. It is in this period that the honorary monikers “Effendi” and “Ustad” became attached to his name. In the mid-1920s, as the commercial recording industry picked up in Baghdad, Azuri became associated with the transnational Baidaphon label, and in 1928, invited him to record in their Berlin studio. This trip marked the beginning of Ezra’s international career, which, as we shall see, was relatively short-lived. During these years other recording labels in Baghdad also released his original compositions on shellac discs.

Participation in the Congress of Arab Music in Cairo in 1932 as a member of—and according to some accounts, as the leader of—the Iraqi delegation, marked a peak in Azuri’s career, an event he will recall with glorified nostalgia in multiple accounts over the rest of his life. What is matters here is that upon returning to Baghdad in late 1932, Azuri’s career becomes burdened with political and professional intrigues which eventually lead eventually to his immigration to British Mandate Palestine between 1934 and 1935. By early 1936, he settled in Jerusalem where he will remain for most of the rest of his life. As far as we know, he did not leave Palestine/Israel until his death.

Ezra’s settling in Jerusalem coincidentally aligned with the opening of the Palestine Broadcasting Service (PBS), a venue that offered him not only a modest steady income, but wide exposure to a large public, both Jews and Palestinians. Although they lasted an average of fifteen minutes each, his “Oriental Hebrew Songs” programs within the Hebrew section of PBS, also opened a set of relationalities within the Jewish community in Palestine for Azuri. For example, it led, for example, to the establishment of a non-profit organization, the Association for Oriental Hebrew Song, centered on supporting his work. The PBS also put Azuri in contact with Palestinian and Arab musicians from nearby countries who had gravitated to the new station in Jerusalem, leading to a variety of collaborations with Muslim and Christian colleagues then active then in Palestine. These collaborations occurred as intercommunal relations between Arabs and Jews in Palestine deteriorated to a boiling point, ending with the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine in November, 1947. The demise of the British Mandate of Palestine on May 14, 1948 and the subsequent war marked the closing of a unique chapter in Azuri’s life, as following these dramatic events the pan-Arab culture to which he intimately belonged, (and its national overtones), was recast as the culture of the enemy.

The establishment of Israel in 1948 brought about the emergence of a new social reality Azuri was forced to navigate. At the same time, several of Azuri’s intimate acquaintances from the Mandate period became brokers in the political and cultural scene, providing him recognition and respect. For example, one of his supporters, Yitzhak Ben Zvi, became the second President of Israel, and Ezra was often invited to play at the presidential residence (with fellow Iraqi violinist Daoud Akram) on Saturday nights. Aharon also found a certain degree of continuity in his employment on the newly created Israeli state radio—Kol Israel—which replaced the PBS station and offered him a slot similar to PBS’ “Oriental Music in Hebrew” programming. Moreover, in the course of time, Kol Israel developed an Arab department as a tool of communication with, and overt propaganda aimed at, Palestinians who remained within the borders of the Jewish state and surrounding Arab countries. With this development Azuri’s role at the station grew, as he was put in charge of developing the Voice of Israel in Arabic’s Arab music ensemble. The relocation of a substantial cadre of professional Jewish musicians, a good number from Baghdad but also from Egypt and Syria, put Aharon in a new role as a “gray eminence” patron in charge of the employment of his newly-arrived younger colleagues.

The eventual establishment of the Arab Music Orchestra of Kol Israel was a prominent achievement for Azuri. It eventually also brought about the demise of his career, as a new generation of Arab musicians in Israel and shifting aesthetics eclipsed him. His retirement in 1967 ended the final chapter of Azuri’s career as an active performing musician, composer and arranger. Aharon outlived his formal retirement from the public eye for almost three decades. This long period was marked by sporadic bursts of interest that new interlocutors and students took in him, his legacy and his well-being. At the same time, during this long period of retirement, Ezra Aharon became an object of a remarkable academic interest. Two scholars, Esther Warkov and Amnon Shiloah “rediscovered” him, interviewing, writing about him and sporadically inviting him to play at conferences and special events. In addition, young artists issued a new recording of several of his works under his supervision. These events, celebratory as they were, recycled early narratives that about Azuri, characterized by a tendency to emphasize his Jewishness at the expense of his Arab identity and cultural leanings.

Ezra Aharon’s death did not lessen the posthumous interest on him. The Israeli radio dedicated a substantial program to his memory; several of his Hebrew-language recordings were rereleased in an album dedicated to his work, and some of his piyyutim were revived in live performances celebrating his memory. A decisive event that allowed the dramatic expansion of our understanding the complex forces at play that have shaped of Azuri’s biography and musical contributions, was the incorporation of his archive to the National Library of Israel in 2015. This rich archive offered us a unique opportunity to reassess Azuri in a new, and we hope more critically expansive, light.

__________________________________

[1] Throughout this biography we employ the simplified transliteration of this Arabic first name, Azuri.

[2] NLI, Mus. 294, N1.